Crossed Wires

by Andrew Robb

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", March 1987, page 16

This article was sent to us by Jack Hayes, Pakenham, Ontario, and appeared in

HORIZON CANADA, The New Popular History of Canada magazine. It is being reprinted with

the permission of the Center for the Study of Teaching Canada/Le Centre d'Etudes

en Enseignement du Canada, Education Tower, 1070 Laval University, Ste-Foy,

Quebec G1K 7P4

Prospectors, trappers and other travelers in the wilderness of north-western

British Columbia still occasionally encounter the scattered remains of one of

the 19th century's most ambitious schemes. Rusty wire, broken insulators and

overgrown trails are the relics of a project that at one time captured the

imagination of much of the western world.

The Collins' Overland Telegraph

Project was as much a part of the technological history of the mid-19th century

as the silicon chip is of the later 20th. Born of the desire to conquer distance

and speed communication, the project used the high technology then available --

the electric telegraph.

The dream of linking cities and continents with strands

of telegraph wire was a passion of many of the leading engineers and businessmen

of the day. Cyrus Field, the American financier who was responsible for the

laying of the first successful Atlantic cable in July 1866, is well known. Perry

McDonough Collins, an entrepreneur and visionary of equal stature, has slipped

into relative obscurity. So, for that matter, has the contribution that Collins

and his work made to the early development of British Columbia.

|

Telegraph station, Bulkley Valley, 1866. Today, when we

can pick up the

telephone and dial Moscow, it is hard to imagine a time when worldwide

communication took weeks, even months The Collins Overland Telegraph was an

attempt to speed up communication between North America and Russia by stringing

a line between San Francisco and Siberia. The painting is by J. C. White, an

artist attached to the construction party.

|

Samuel Morse's

invention of the electric telegraph in 1835 marked the start of a communications

revolution. After the first short line was completed in 1844 between Washington

and Baltimore, most of the settled parts of North America were soon linked by

telegraph wire.

In Europe there was a similar and rapid expansion. Morse Code, by the early 1860s, had become an international

language, and the telegraph had transformed conceptions of time and distance.

Newspapers now carried despatches 'by wire," bringing immediacy to events

that formerly were known days or weeks after the fact.

By the early 1860s, the

one remaining challenge to the telegraph engineers was the establishment of an

intercontinental link. Americans and Europeans, facing each other across the

broad but familiar Atlantic, thought first of a submarine cable. Since the mid-1850s, insulated submarine cables had linked England and the Continent, but the

Atlantic cable project seemed doomed to failure. Attempts had been made since

1857 to lay a cable, but had failed because of broken wire and the inability to

transmit over long distances on an underwater cable. Many were convinced that an

Atlantic cable would never work.

Perry Collins proposed an alternative. Why not

go west to Europe rather than east? North America and the Eurasian land mass

were separated by only the narrow waters of Bering Strait if one looked to the

northwest. To be sure, there were also thousands of kilometres of virtually

unexplored wilderness to be crossed, but this, though formidable, was not

insurmountable in either human or technological terms.

Scouting the Terrain

It was in many ways natural for Collins to think in

terms of a western route linking the continents. Born in New York in 1813, his

early adult years were spent as a law clerk in New Orleans and New York City.

Like thousands of other young men, he had followed the gold rush to California

in 1849. More suited to business than mining, he was soon a partner in a gold

brokerage firm and increasingly aware of the commercial possibilities of the

West.

|

A View of Canada Going to Pieces

Frederick Whymper, an English artist, joined the Collins' Overland Project as

an illustrator in 1866. He recounted his experiences in a book, Travel and

Adventure in the Territory of Alaska, published in London in 1868.

Commenting on

the United States' purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, he had this to say

about the significance of the move for the future of Canada:

"There are

many, both in England and America, who look on this purchase as the first move

towards an American occupation of the whole continent...

"We [Britain] shall

be released from an encumbrance, a source of expense and possible weakness; they

[the U.S.], freed from the trammels of periodical alarms of invasion, and

feeling strength of independence, will develop and grow; and speaking very

plainly and to the point - - our commercial relations with them will double and

quadruple in value... That it is the destiny of the U.S. to possess the whole

northern continent I do believe..."

|

Terminal station. Before it was abandoned, the Collins line

stretched

from New Westminster (shown here) to the Skeena Valley in northern B.C. |

By the mid-1850s, Collins, together w ith entrepreneurs like Milton Latham and William Gwin, both later to become senators from California and

influential allies, had become convinced that the North Pacific and Asiatic

Russia were a rich potential field for American commerce. Collins had himself

appointed American "Commercial Agent for the Amur River" and visited

this frontier region of the Russian Empire, becoming increasingly convinced of

the commercial possibilities for the United States. His book, Voyage Down the

Amoor (1860) described in glowing terms the opportunities for American trade

and technology.

Man in charge. Edmund Conway (seated centre), a veteran of the American Civil

War, was placed in charge of construction through British Columbia. He traveled

on foot up the Fraser Valley from New Westminster to Hope laying out the route

of the southern section. Partly at Conway's urging, the government agreed to

build a wagon road from the coast to link up with the already completed Cariboo

Road in the interior. The telegraph could hove a right-of-way along the road and

would only have to bear the expense of erecting poles and stringing wire. |

The commercial potential of a telegraph linking Europe and

America via Bering Strait was also obvious to Collins. Whoever controlled the

huge volume of telegraph communications between the continents was assured

healthy profits. If such a line could also open Russian America, British

Columbia and Asia to American commerce. so much the better.

His first thought

was to promote a line from Montreal, across Hudson Bay Co. territory and through

Russian America to Bering Strait. This would be the shortest route and would

avoid the mountainous, difficult terrain of British Columbia. In Montreal,

Collins formed the Transmundane Telegraph Co., and began to look for support for

the scheme.

Despite the personal enthusiasm of backers such as Sir George

Simpson, overseas governor of the HBC, he had little success. Neither the

Canadian nor the British governments were interested in providing subsidies.

and the HBC would not contemplate the large capital outlay required. By 1860,

Collins was looking to the United States for support, convinced that the

Canadians would not move fast enough to seize the opportunity.

His timing was

good. In 1859 and 1860 the Western Union Telegraph Co., led by its dynamic

president, Hiram Sibley, was in the process of absorbing smaller rivals and

establishing a telegraph monopoly in the United States. It was also lobbying

Congress for support in building a transcontinental line to California, and saw Collins' scheme

as a

natural complement to its own.

'Living and Thinking Wire'

When the Western Union's wire reached San

Francisco in late 1861, Collins' plans were several thousand kilometres closer

to realization. The Civil War, which had shattered the union, made both the

urgency of an intercontinental link, and the difficulty of negotiating with

the British and Russians, more apparent. Collins spent the next two and a half

years negotiating with British, Russian and American officials to secure the necessary rights of way and support. By late 1864, his efforts succeeded,

and the Collins' Overland Telegraph Project was born.

Financed by a special

issue of Western Union shares, the project was of awesome proportions. A line

was to be built from San Francisco to Bering Strait where a short submarine

cable would be needed. From there, the line would be built south to the Russian

Pacific port of Nikolaevsk where it would connect with Russian lines.

Collins

received $100,000 for his negotiations and substantial amounts of stock in the

new company. As he told the Travellers' Club of New York in December 1865, the

future looked good for Western Union: ''Like the British Empire upon which the

sun never sets, our messages... will never cease; and those who can look sharply

into figures may be able to estimate the earnings of the Overland line." As

Senator Latham of California, an ardent supporter of Collins, put it: "We

hold the ball of the earth in our band, and wind upon it a network of living and

thinking wire.''

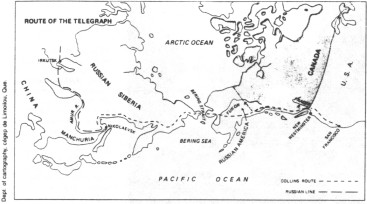

The Collins line.

Construction was divided into three sections: B.C., Russian

America (Alaska) and Siberia. Work in Siberia hardly got going before the project

shut down. |

The organization and operation of such a gigantic scheme

required the experience of military men. In late 1864, there was no shortage of

available talent. Col. Charles S. Bulkley, a veteran of the Military Telegraph

Corps, was the man chosen to head the project. Quickly, he recruited a staff

which included many who would later achieve considerable renown. Edmund Conway, another Telegraph

Corps veteran, was in charge of the British Columbia work. Others, such as

George Kennan. Franklin Pope and W. H. Dall would make valuable contributions to

the American knowledge of Alaska and Asiatic Russia.

Charles Bulkley.

He was in charge of the entire project. |

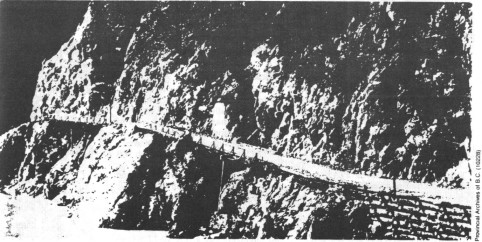

Cariboo Road. Wherever possible, the Collins line followed the Cariboo Road,

constructed in the early 1860s to give access to the goldfields of the interior. |

|

Stringing the

line. Two more views of telegraph construction by J.C. White.

Bottom, lines crossing a lake to one of the stations which were built every 40

km. Top, a pack train bringing in wire and other supplies. Whenever possible,

the company hired Indian and Chinese labourers who accepted the low wage of $15

a month. White colonists resented this policy, but the company persisted.

Conditions were hard and the rough colony was not to everyone's liking. Edmund

Conway complained that "one encounters nothing but heavy timber, rum mills,

broken miners, English aristocrats, loafers and swindlers... Banishment in

Siberia "is a paradise in comparison to this place." |

|

|

Road to Russia.

Another view of the Cariboo Road, which the telegraph line

followed up the Fraser Canyon. |

The project was organized along

military lines, and even had a naval branch to transport supplies to the widely

scattered survey and building parties. Three construction divisions were

established -- Siberia, Russian America and British Columbia -- each with their

own commanders, surveyors and labourers.

Quick Work

Except in southern British

Columbia, the line would pass through territory seen only by the Native people

and a few fur traders. The natural obstacles were of mammoth proportions.

Despite this, the project made surprisingly rapid progress.

By March 1865, New

Westminster was connected and work was begun on stretching wire up the Fraser

Valley and through the difficult terrain of the Fraser canyon. That year, the

line was completed to a point about 30 km north of Quesnel, when winter brought

work to a halt.

Surveyors, axemen, Chinese labourers and engineers cut a line

10-12 metres wide, along which poles were placed every 20 metres. At regular intervals,

cabins were built for supplies and telegraph equipment. In both Siberia and

Russian-America, the survey had proceeded quickly in 1865. When work began early

the following spring, the experienced crews made rapid progress. By July 1866,

the entire line had been surveyed, and the necessary supplies put in place.

In

B.C., the line had been completed to the Skeena Valley, and crews were pushing

north quickly. Even Victoria saw a small measure of its insularity ended as a

line reached the island city in April. It seemed as if the project could not be

stopped, so rapid was the progress.

Then, to spoil the mid-summer euphoria, came

potentially bad news. An Atlantic cable had been laid, and was working.

Taking a

nervous 'wait-and-see' attitude, the company halted construction work in B.C.,

but in the more remote regions of Russian-America and Siberia. work continued.

Atlantic cables had failed before, surely this one would too. By early 1867

though, the cable was still working. The end had come for the Overland Telegraph

Project.

Not a Total Loss

Work crews hung black crepe on telegraph poles in mourning.

Some equipment was loaded on company ships and returned to San Francisco, but

much more equipment was simply abandoned or sold to the Natives. For years

afterward, travelers reported Alaskan Natives awkwardly drinking tea out of

green glass insulators.

Although much was lost with the collapse of the project,

much also had been gained, especially in B.C. External communications had been

vastly improved and a connection made with the outside world. It would be

another 20 years before an all-Canadian telegraph line reached the Pacific.

British Columbia would get news of Canadian Confederation via an American wire

service.

Both Western Union and Collins continued to prosper despite this

setback. Collins lived comfortably in San Francisco and New York until his death

in 1900 at the age of 87. When, in 1867, American Secretary of State William

Seward arranged the purchase of Alaska, he was grateful to the scientists of the

telegraph project for their enthusiastic endorsement of his bargain with the

Russians. Thanks to the Collins project, they were part of a tiny group of

Americans who were fully aware of the richness of Alaska's resources.

Yukon telegraph.

This line was the heir of the Collins project. The Yukon line was constructed in 1899 across the Yukon territory, and two years

later it was extended south to Quesnel in central British Columbia. Construction

techniques did not differ much from those employed on the Collins line. Wire was

strung on poles cut for the purpose, or on living trees topped and trimmed where

they grew. The wire was carried up the pole and tied to a glass or porcelain

insulator. Insulators prevented loss of electrical current if wire touched the

pole. |

|